The film „Women Composers“ - a journey into the European past

- a discovery of great lost treasures of music and of impressive women as “role models“

I have known Kyra Steckeweh since 2004. Together we have realized several artistic and musical projects and experimental music videos. In the autumn of 2016, we had the idea to visualize biographical details of Mel Bonis and Lili Boulanger, in short clips for her concerts.

I originally estimated a two-day shoot in Paris for two short, five-minute videos. But, that was just the beginning of a thrilling discovery trip and adventure that took Kyra and me all over Europe. Our heroines are widely unknown to the public. Soon we were convinced that short clips would be inappropriate, since the stories behind the women and their music, were just too exciting.

I thought that TV broadcasters would be interested in joining our project. I was a bit surprised when a major broadcaster told me, that currently only films about living people and artists are being supported, and that there is no interest in films about the dead.

However, the year 2018 has been proclaimed as the “European Year of Cultural Heritage“; how can it be that without including the “dead“?

It became clear that Kyra and I would be completely on our own with this project. The film was financed privately; a low budget inspires creativity. Many participants waived their usual fees and thanks to a successful crowd-funding on startnext.com in January 2018, around 10,000 Euros were donated. In this context we wish to gratefully mention DIGIM GmbH from “Halle an der Saale“. They have supported us intensively in the completion of the film.

It became clear that Kyra and I would be completely on our own with this project. The film was financed privately; a low budget inspires creativity. Many participants waived their usual fees and thanks to a successful crowd-funding on startnext.com in January 2018, around 10,000 Euros were donated. In this context we wish to gratefully mention DIGIM GmbH from “Halle an der Saale“. They have supported us intensively in the completion of the film.

By studying the biographies of these four very different women it became clear to me how patriarchal our perception still is to this day. Despite my great interest in classical music, I actually only knew Clara Schumann as a composer. On the other hand I could not imagine that only men would have written classical music. Female singers are recognized in classical music, some are famous and very big stars, but it seems that women who write classical music for an orchestra, or chamber music are seen from a completely different perspective.

In modern music, such as pop, rock and all experimental forms, this changed decades ago and female composers are, in contrast to classical music, completely accepted. Imagine for a moment that, before producing a new CD, Madonna would have to ask her brother’s or ex-husband’s permission and financial help, in order to get a record company to print her music on a CD. Then think, how Fanny Hensel must have felt having to ask her brother to allow her to publish her compositions. It is hard to imagine, is it not?

In modern music, such as pop, rock and all experimental forms, this changed decades ago and female composers are, in contrast to classical music, completely accepted. Imagine for a moment that, before producing a new CD, Madonna would have to ask her brother’s or ex-husband’s permission and financial help, in order to get a record company to print her music on a CD. Then think, how Fanny Hensel must have felt having to ask her brother to allow her to publish her compositions. It is hard to imagine, is it not?

It was interesting to observe how the contacted program makers of all major German concert halls „ducked low“ when we asked them for an interview for our film. Tobias Niederschlag, the executive program director of the „Leipzig Gewandhaus“, was the only one who had the confidence, I would almost say the courage, to face the camera and answer our questions.

It was interesting to observe how the contacted program makers of all major German concert halls „ducked low“ when we asked them for an interview for our film. Tobias Niederschlag, the executive program director of the „Leipzig Gewandhaus“, was the only one who had the confidence, I would almost say the courage, to face the camera and answer our questions.

On the other hand, we were stunned by some doors opening completely unexpected. For example we were spontaneously invited to film in Mel Bonis’ former residence in Sarcelles, when we wanted to take pictures of her bust standing outside of a small museum near Paris.

Lost treasures

A few weeks later when we visited Mel Bonis’ great-granddaughter Christine Géliot, who showed us a huge metal box in her attic. To our great astonishment the original manuscripts of her great-grandmother came to light - what a treasure!

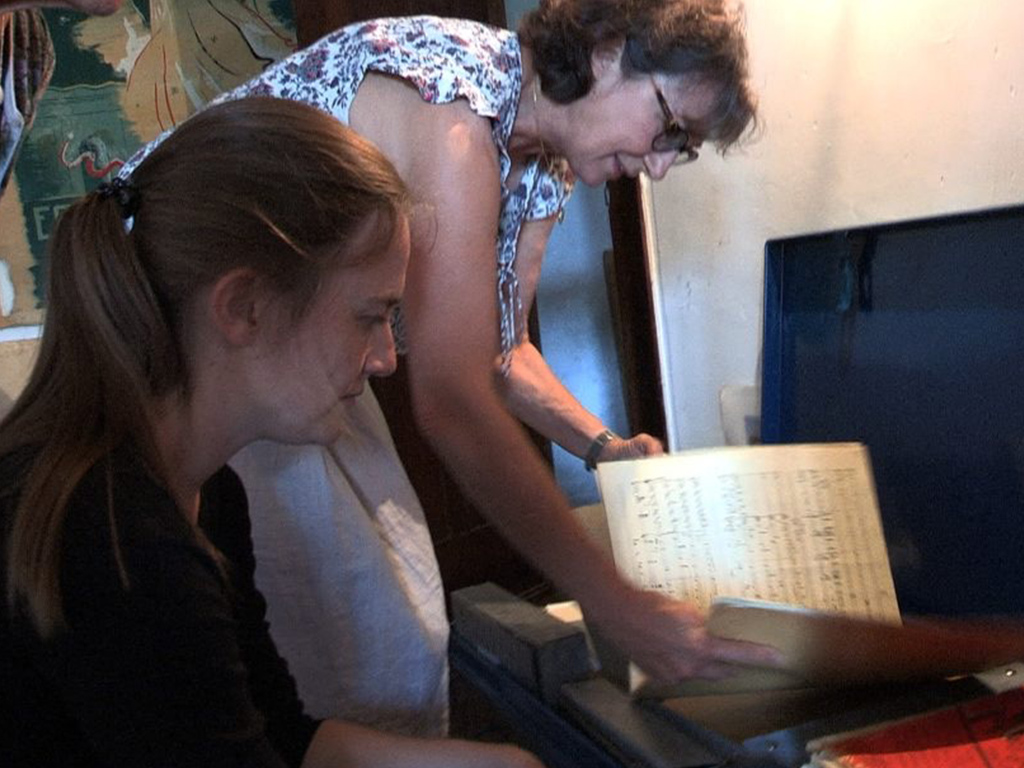

Of course we also wanted to film Emily Mayer’s autograph on the D-minor Sonata in the Berlin State Library, where her belongings are kept. We were irritated when all our requests were unrelentingly turned down. Only when Barbara Schneider-Kempf the Director intervened personally, Kyra was allowed to see the autograph in her office and I was given permission to capture this scene with the camera.

Unfortunately we had no luck in Rome. The French Academy in the Villa Medici initially did not respond to our requests at all. Then, upon a further request officially denied filming and an interview. This is the site of Lili Boulanger‘s greatest triumph before she died at the young age of 24. It was quite a different scenario at the German Academy in the Villa Massimo. After a short consultation we were received in a very friendly manner and were allowed to work there for two days.

The research on Emilie Mayer was particularly exciting. We knew that she had been buried in April 1883 at the Trinity Cemetery in Berlin-Kreuzberg, but that her grave was considered lost.

The research on Emilie Mayer was particularly exciting. We knew that she had been buried in April 1883 at the Trinity Cemetery in Berlin-Kreuzberg, but that her grave was considered lost.

However, our historical expert Dr. Jörg Kuhn did not give up, and so thanks to him and his persistence we actually found the grave during our filming work. We believe that this important citizen of our city should be honoured by the setting of a memorial; a new project, which we will propose to the Berlin Senate.

The dealings in Friedland, Emilie Mayer‘s hometown, were rather disappointing. The museum of local history recently removed the few exhibits they had from their display. There is nothing left. It is too bad when nobody is interested in a historical work-up about such an unusual woman! In Berlin’s address register, she was listed with the professional title „women composer“. As a single and independent woman in the 19th century, she really was an impressive „role model“!

The dealings in Friedland, Emilie Mayer‘s hometown, were rather disappointing. The museum of local history recently removed the few exhibits they had from their display. There is nothing left. It is too bad when nobody is interested in a historical work-up about such an unusual woman! In Berlin’s address register, she was listed with the professional title „women composer“. As a single and independent woman in the 19th century, she really was an impressive „role model“!

In social science research, the English term „gender“defines the socially and culturally determined roles, rights, duties, interests and resources of men and women whose perceptions it aims to achieve. A comparable term is unknown to me in the German language.

At the moment, experts, politicians and other interested parties are all arguing about how to correctly portray both (in Scandinavia: three genders); whether with asterisks, lower key or capital letters or quotation marks. It is reassuring that the terms “women composers, women conductors and female pianists“ have meanwhile come into use of the German language and that there are women who practice such professions - independently of their brothers, fathers and husbands and their approval.

I realize that this film about these four women composers really only is the beginning of a series of documentaries about women composing music. Kyra and I are already working on further episodes, on a series and on individual portraits. In the future these could also be used for music lessons in schools and other educational institutions.

We do not only think about historical educational work. We also think about inspiring and encouraging the next generation to listen to and appreciate classical music and also, to create it. Together we are confident that in the coming years we will close many gaps and will meet more great and wonderful women.

On this note see and hear for yourself!